The Pillars Fund team is still buzzing with renewed energy and inspiration. On September 8, Pillars kicked off our three-day 2023 National Convening, gathering nearly 100 Muslim leaders, artists, and supporters in Atlanta. This was the first time in four years that we were able to gather the full breadth of the Pillars’ community together, and it was a special moment. The excitement and camaraderie among our attendees—some longtime friends, others new acquaintances—was palpable throughout the weekend. It was our honor and joy to facilitate a space for these change makers to imagine and feel rooted together. And we can’t wait to tell you more about it.

Welcome Dinner at the Museum

It didn’t matter where in the country you were from, the warmth, hospitality, and graciousness of our Atlanta grantee partners and host committee members made the Pillars Fund community feel at home in their city.

We started the weekend with a welcome dinner at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, a place of hard truths and deep reflection that highlights this country’s history of violence and injustice. The museum uplifts the legacy and efforts of Black communities and people of the global majority to push for social change and create a more equitable world.

Pillars President and Co-founder Kashif Shaikh grounded our gathering in joy and connection before introducing Pillars Program Director Amirah Fauzi, who highlighted the abundant talent in the room, including grantee leaders facilitating panels and a Pillars Artist Fellow screening his South by Southwest-award-winning film. Pillars Board Member Saleemah Abdul-Ghafur also welcomed the room to Atlanta and shared why she was excited to have us in her city.

We shared food and swapped stories before exploring the museum’s exhibits on the history of civil rights, which highlighted both the powerful resistance happening and the racist horrors that made it necessary. We witnessed the papers and artifacts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., become immersed in panoramic footage of the 1963 March on Washington, participated in an audio exhibit that simulated the brutality of a lunch counter sit-in, and much more.

Opening Remarks + Poetry Performance

Our programming continued Saturday morning at the Westin Peachtree Plaza. Pillars Vice President Kalia Abiade first rooted our gathering in the legacy of our host city’s Black civil rights legends who have passed the torch to contemporary Southern organizers and activists. Her remarks were followed by a moving poetry performance from Pillars Muslim Narrative Change Fellow Omar Offendum. “Habibi, be content with what you have. Matter of fact, rejoice in it,” he recited. “When it’s all said and done, happiness is but a choice, innit? Learn to love the journey and find your voice in it.”

“When it’s all said and done, happiness is but a choice, innit? Learn to love the journey and find your voice in it.”

Community Connection

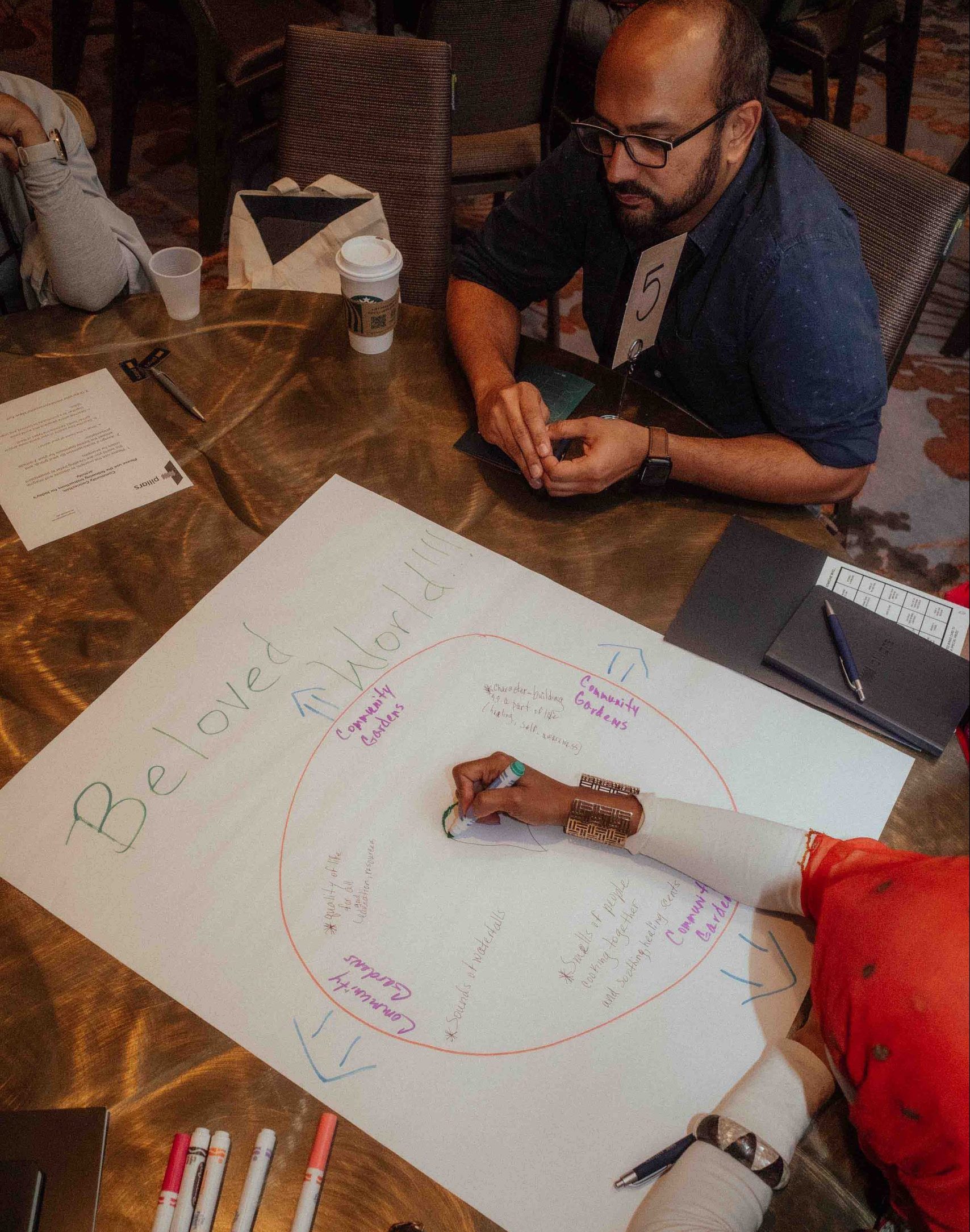

To further introduce and connect our group, Pillars Senior Program Manager Maryam Abdul-Kareem and Program Associate Mawish Raza led an interactive exercise where attendees imagined, created, and illustrated the worlds that they would want to live in. Both our artistic skills and imaginative brains were put to the test!

Then our breakout sessions began:

Listening as a Creative Act: Building the Storytelling and Story-Listening Capacity of Our Movements

Oral historian and educator Zaheer Ali led a workshop exploring how attentive, relational, and generative listening increases knowledge and nurtures community. Zaheer explained that all of us can hear the same thing, yet hear it differently. So much depends on how much we know about what we’re hearing and how much we’re touched by it. The more context we have, the better listeners we might be. The session resulted in the creation of a playlist that could only have come from the people in the room. You can read Zaheer’s essay on “Listening as a Creative Act” in “Khayál: A Multimedia Collection by Muslim Creatives.”

Ask a Funder Anything

During this closed-door session, Pillars staff, trustees, and funders left the room so grantee partners and fellows could have a candid conversation with Maheen Kaleem, Vice President of Programs and Operations at Grantmakers for Girls of Color. Attendees had the opportunity to ask about anything: funding, resources, power dynamics, and any other philanthropy-related topics. After the conversation, participants said they were already thinking of how their organizing practices can be applied in their grant seeking approaches.

Practicing Allah-Centered Love

The hard work of imagining and striving toward brighter futures can often result in burnout and feelings of loneliness and self doubt. Angelica Lindsey-Ali, also known as The Village Auntie, led a spiritually enriching workshop to strengthen our connection with Allah and teach how self-love can be a powerful tool to return to a sense of purpose and worthiness. She reassured us that our “existence is already validated by the love, grace, and mercy of Allah” and that we “don’t have to do anything, … be anything, say anything, … produce anything in order to be validated.” It was an honor to be in such a supportive and expansive space.

“[Our] existence is already validated by the love, grace, and mercy of Allah.”

Atlanta in the Spotlight: Organizers and Activists on Local Issues

Moderated by Hibah Berhanu of the Georgia Muslim Voter Project, this conversation created space for activists working with Atlanta communities to share more about their organizing and community lawyering efforts. Panelists included Juilee Shivalkar from Project South, working on the campaign to Stop Cop City, and Maha ELKolalli, an attorney who works closely with the family of Imam Jamil al-Amin to free him. The panel touched on an overview of each campaign while highlighting powerful stories and reflections. Additionally, the discussion surfaced some difficult but necessary conversations about the erasure of the long and powerful legacy of Black Muslims’ efforts in the fight toward freedom, the wounds many experience because of systemic erasure, and the importance for the larger Muslim community to support freedom movements. This session reminded us of the importance of showing up and building community with specificity, compassion, and understanding which communities this labor often falls on.

The fight for these campaigns and the work to address injustice continues. These two campaigns left the Pillars community with ways we can continue to support:

- Imam Jamil, an incredible force inside and outside the Muslim community and a vital figure in this country’s movement for social change, has been wrongfully imprisoned for more than two decades. The Free Imam Jamil campaign is asking for a public push for transfer as they focus on exoneration. You can find a list of action items regularly updated by Imam Jamil’s team here.

- The City of Atlanta has leased 381 acres of Weelaunee Forest to the Atlanta Police Foundation for a militarized police training facility called Cop City. Learn more about the Stop Cop City campaign and how to support it on their website, and take a look at the legal and advocacy work our grantee partner Project South is pursuing on this issue.

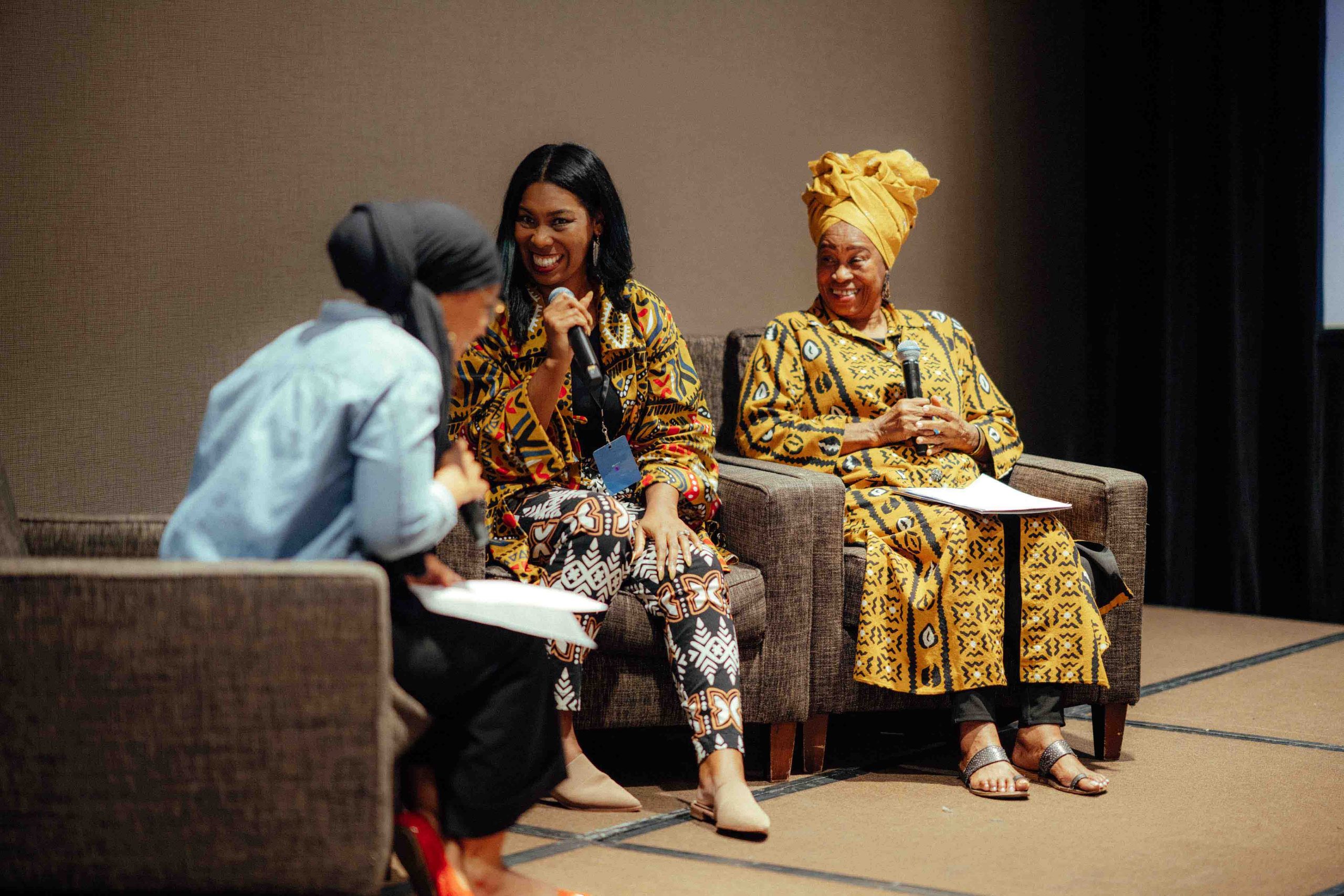

Intergenerational Dialogue: Mother-Daughter Organizers Talk Family Legacy and Advocacy in the South

Pillars VP Kalia Abiade moderated a special panel with Sister Okolo Rashid of International Museum of Muslim Cultures and Aseelah Rashid of IMAN Atlanta. The mother-daughter duo discussed their family history of community building, the legacy of organizing in the South, and sustaining movements across generations. Sister Okolo shared that “Jackson, Mississippi, and the South as a whole, represent the history of the blood, sweat, and tears of the African people that were brought over as enslaved people.” She added that “the South, and Jackson, represents a ground zero for the movement and the struggle that African Americans and others have engaged in.”

Aseelah reflected that growing up with parents who were freedom fighters meant doing intimidating things: “I was shaped in a way to seek out or to be really aware of moments … when someone is needing to step in, when someone is needing to speak up.” She spoke about being the product of her community’s activism: “The reason why I’m able to even talk about how we’re moving in community and building in community,” she said, “is because I am literally the fruit of that labor of that community.”

“The South, and Jackson, represents a ground zero for the movement and the struggle that African Americans and others have engaged in.”

Closing Reflection

Pillars Board Member Noorain Khan closed out our sessions at the Westin by sharing her reflections from the day. “How can you capture hours that were so abundant, so full of joy, curiosity, connection, revelation, exploration, divinity, and understanding?,” she shared. “As someone whose day job involves your constant, sometimes drab, conferences and convenings, the suite of sessions here and the ways in which you all showed up in them, was also magical, communal, and prompted introspection and evolution.”

Dinner at Springreens at Community Cafe

Sister Jamella Jihad and her team graciously offered us their beautiful, candle-filled space and halal soul food for dinner. Lovingly made mac and cheese, succulent beef ribs, tangy mango ginger juice, and sweet bean pie—it really was that good. You have to stop by the next time you’re in Atlanta.

Mustache Film Screening + Talkback

After dinner, we wrapped up a long, productive day by screening “Mustache,” a South by Southwest-award-winning film by 2022-23 Pillars Artist Fellow Imran J. Khan. “Mustache” tells the story of a 13-year-old Muslim boy who must navigate the dynamics of his new public school. The screening was followed by a short talkback with Imran and Pillars Program Manager Aya Nimer. Many in our audience felt an emotional connection to the film, and a teen in the crowd even confirmed that the film rang true to her experiences as a young Muslim.

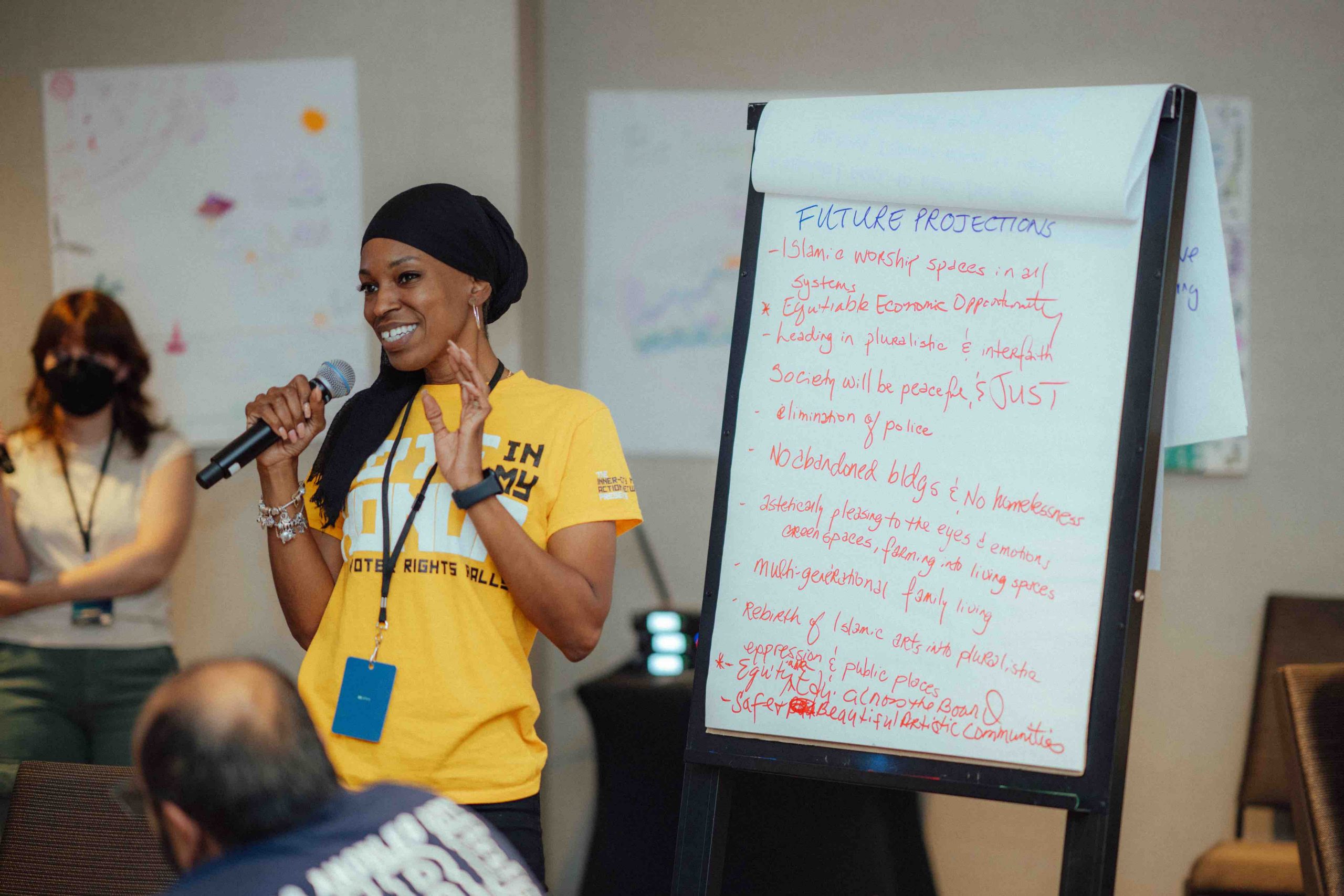

On Sunday, we concluded our programming with a collective visioning session:

Future Visioning

Nadra Widatalla, a community organizer and 2022-23 Pillars Artist Fellow, set the stage with a reflection, reading from her personal journal from a recent trip to Europe. She went on her trip seeking to better understand freedom. “Freedom isn’t a destination,” she wrote. “It’s a feeling… the feeling of arrival.”

Next, Robert Earl Sinclair of Future Architects took the helm, helped our group weave together narratives of the past before writing a narrative about our futures. The session started with a playful speculative history that pondered what could have been if the American Indian Movement had successfully taken over Alcatraz, if Tupac had lived and become president, or if there was a Muslim version of “Friends” in the ’90s. Our groups then imagined what a just future for Muslims could look like. Imaginations included fully funded art programs; mental health care for all; abolishing police, prisons, borders, white supremacy, and class; abundant greenery and wholesome food; wholly inclusive Islamic worship spaces; a four-day work week; and Muslim holidays being open celebrations for everyone in society.

Robert encouraged our attendees that these imagined futures are achievable through the work they are already doing: “Our inflection point is now. We are laying the foundation for this kind of radical aspirational change just by meeting, talking, synergizing.” It felt like the future was in the room.

“Our inflection point is now. We are laying the foundation for this kind of radical aspirational change just by meeting, talking, synergizing.”

IMAN-led Atlanta Tour

Pillars grantee partner IMAN Atlanta graciously hosted the Pillars community for a fun-filled afternoon bus tour of their home city. We saw the birth home and adult residence of Dr. King, the campuses of three of Atlanta’s HBCUs, Spelman College, Morehouse College, and Atlanta Clark University, and the block where IMAN plans to build a community market to offer fresh produce to neighborhood residents.

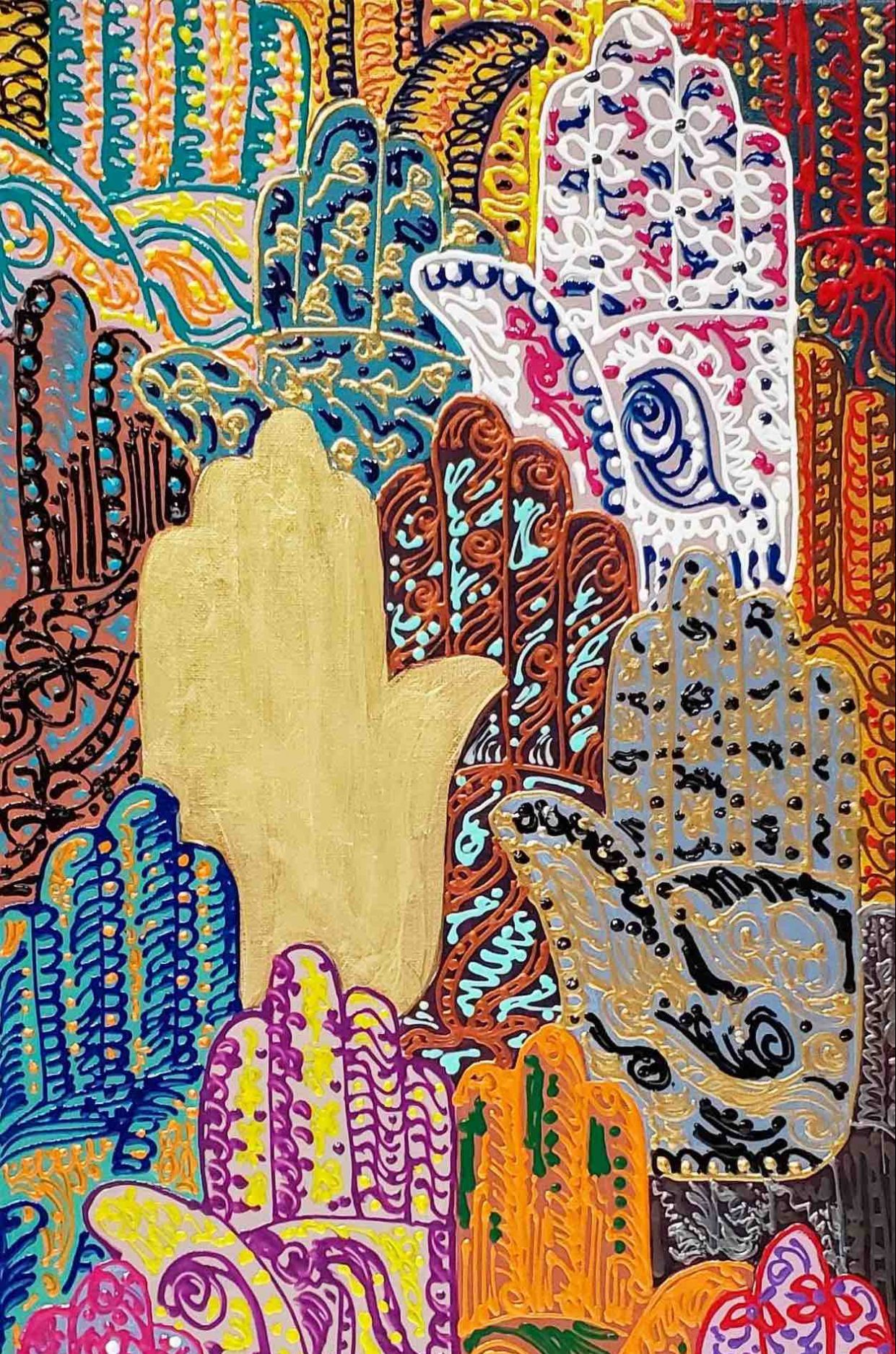

IMAN’s work in Atlanta includes their Green ReEntry program, which offers housing, education, and training to those returning to society after prison. With sweet watermelon and peach italian ice in hand, our group heard from the folks on the ground at IMAN about how this program is making a difference for people in their community. We couldn’t leave without admiring the beautiful mural at the front of their Green ReEntry apartments, designed and painted by Kelly Crosby, a local artist and Pillars featured artist for this convening.

We featured a beautiful hamsa hands design of Kelly’s on postcards given to every one of our attendees. During the weekend, they could write a message on a postcard and the Pillars team would gather all the cards and mail them post-convening. So many lovely messages left Atlanta!

View this post on Instagram

Until Next Time

Thank you to our incredible attendees for bringing their energy and presence to the convening and to our brilliant host committee, who warmly welcomed us to their city. We left Atlanta filled with gratitude, unforgettable memories, and lifted spirits to continue Pillars’ mission of creating spaces where Muslims can create, collaborate, and feel empowered to shape a future filled with equity and justice for all.